Heritage protection

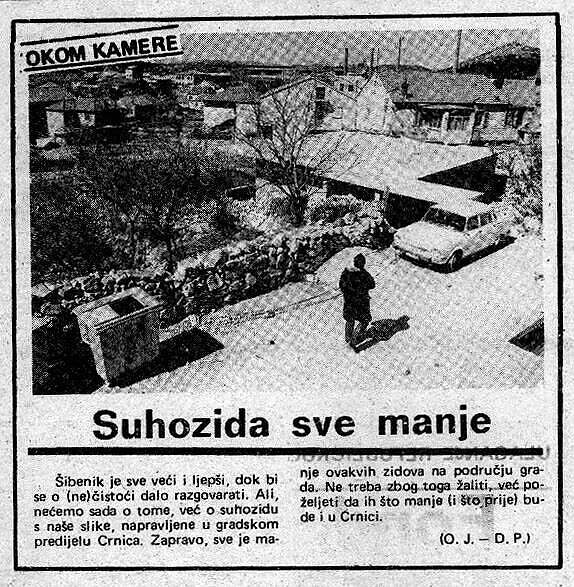

Lately, we have often received complaints about the demolition of dry stone walls – from a neighbor knocking down a shared wall to a utility company destroying dry stone walls along a public road. What do we think about it, what are the legal implications, and what can you do to prevent it? Sometimes it is difficult to witness the disappearance of dry stone structures, but it is important to start with a clear understanding: dry stone walls are an expression of the practical needs of their time. Ever since Illyrian times and even earlier, old walls have been used as a source of building material for new ones. By the end of the 19th century, when many of today’s dry stone walls were constructed, rocky areas and existing vegetation, including olive groves, were often cleared mercilessly to prepare the land for planting vineyards. We are a practical people, and as proud and sensitive as we are to the beauty of our landscapes, when choosing between beauty and utility, we usually opt for the latter. There are countless examples along the entire coast that prove this. The same practical urge that once led to the building of dry stone walls now often leads to their demolition: they occupy space, they no longer provide adequate protection, and their rubble can serve as material for new construction. So the motive is clear. Furthermore, the most beautiful dry stone landscapes were almost certainly the terraced areas near old town cores, and these very landscapes were destroyed in the same way during the 20th century, especially after 1965, with the expansion of Adriatic towns. In one issue of Slobodna Dalmacija from the late 1980s, we found an article welcoming the removal of dry stone walls from the city, probably because to the journalist they symbolized the remnants of backward, rural life.

Today, the situation is different – dry stone walling skills are protected as cultural heritage, and the rural landscape, until recently considered strictly utilitarian and agricultural, is now also recognized for its cultural, environmental, and ecological value. Dry stone walls themselves in Croatia are not protected as immovable cultural heritage; it is their construction skills that are protected. Why is that? If all dry stone walls were protected as immovable cultural assets, millions of plots would have to be entered into the land register, the State would have the right of pre-emption, and for any intervention one would need to request conditions, approval, and supervision from the competent conservation department. All state administrations would probably need to retrain to manage dry stone walls, and it is clear that such a system would not be sustainable. This does not mean that no dry stone structures are protected: 1. Several dozen bunje and other dry stone buildings, several old roads and paths supported by dry stone walls, a few dozen rural units containing dry stone walls, around a hundred prehistoric forts and tumuli, and several cultural landscapes have been designated as individual cultural assets, and their destruction is strictly prohibited and punishable under the Criminal Code. 2. Several towns and municipalities have banned the destruction of dry stone walls in their spatial plans; in these cases, it is possible to report offenders to the municipal police (though we are unaware of this happening in practice). Speaking generally: 3. According to the Construction Act, the removal of any structure – including dry stone walls – must be duly reported to the competent construction authority, and failure to do so constitutes a violation of the law. 4. Any removal carried out without the consent of all co-owners constitutes a violation of property rights. The greatest misfortune of dry stone walls in our country is probably that there are so many of them that most people do not even perceive them as a value or peculiarity – not even those who should protect them by profession, such as conservators, municipal officials, or construction inspectors. Moreover, many dry stone walls are in a rather poor state, and their removal is often perceived not as damaging to the aesthetic of the landscape but as an improvement. These are some of the reasons why we as an association have opted for a proactive approach: to build, restore, and spread knowledge, because trying to address devastation directly would be a Sisyphean task, in which – by focusing on some cases – we would inevitably be unfair to countless others, both past and present. A similar principle applies to UNESCO protection – the skills are safeguarded through education, practice, and restoration.

*

The art of dry stone walling received permanent protection in December 2016 as an intangible cultural asset of the Republic of Croatia, following a three-year period of provisional protection. In 2018, the art was inscribed on the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, as a result of a joint international nomination by Cyprus, France, Greece, Croatia, Italy, Slovenia, Spain, and Switzerland under the title “Art of dry stone construction, knowledge and techniques.” In 2024, this protection was extended to Andorra, Austria, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Ireland.